Black Creek is located within an area renowned for its dense immigrant demographic. The strenuous process that some may face, of departing from a familiar homeland and adapting to a new cultural milieu is inherently challenging. However, amidst this transition, one may find comfort and continuity in the culinary traditions of their heritage. Food transcends mere sustenance or gustatory pleasure; it serves as a conduit, facilitating a reconnection with the ancestral roots and the past lives left behind. Beyond its geographical significance, food assumes the role of a symbolic emblem, emblematic of group identity and cultural belonging.

Canadian diets are not monolithic. They are, however, a microcosm of Canadian history and culture. The diet’s roots extend from Indigenous food systems, colonialism, civil rights and multiculturalism. Food is bound to socio-political and emotional processes that shape what one eats and how they eat it (Rouse and Hoskins 2004, 234). Therefore, economic disparities due to systemic racism and colonialism have their part to play in what one eats. To be simply put, racism can be defined as a structure of power, privilege and dominance made on the basis of one’s racial group (Hicken, Lee, and Hing 2018, 158). Racism allows members of the dominant group to acquire social privilege through the maintenance of beliefs, values, structures as well as behaviours (Hicken, Lee, and Hing 2018, 158). This leaves members of minority groups present within said society to be excluded from privileges and reduces their access to societal resources, such as healthy and nutritious food that is culturally significant to them (Hicken, Lee, and Hing 2018 157-158). According to Risseto (2021), “We have grown up in a society that idolises white foods”. In doing so, it excludes other cultures’ foods and cuisines to be considered as “healthy”.

In 2023, CBC news reported that 1 in 10 people depend on food banks. As inflation and increased food prices have become a daunting reality for several Canadians, access to nutritious and healthy food has become a luxury– a privilege which very few can afford. While expenses soar, wages stagnate, low-income households are unable to afford the basics. Simultaneously, on the occasion that one is able to afford food, they often gravitate towards foods that are heavily processed, neglecting fruits and vegetables, which are frequently genetically modified and treated with pesticides.

Access to healthy, organic, culturally relevant food in Black Creek is severely constrained by its notably higher costs compared to processed alternatives. Local grocery outlets offer limited assortments of organic products, which are often highly priced beyond the means of many residents (Black Creek Food Justice Network, 2019). As food prices escalate, the financial strain on Black Creek’s population intensifies, aggravated by stagnant or diminishing wages, particularly impacting low-income households (Black Creek Food Justice Network, 2019).

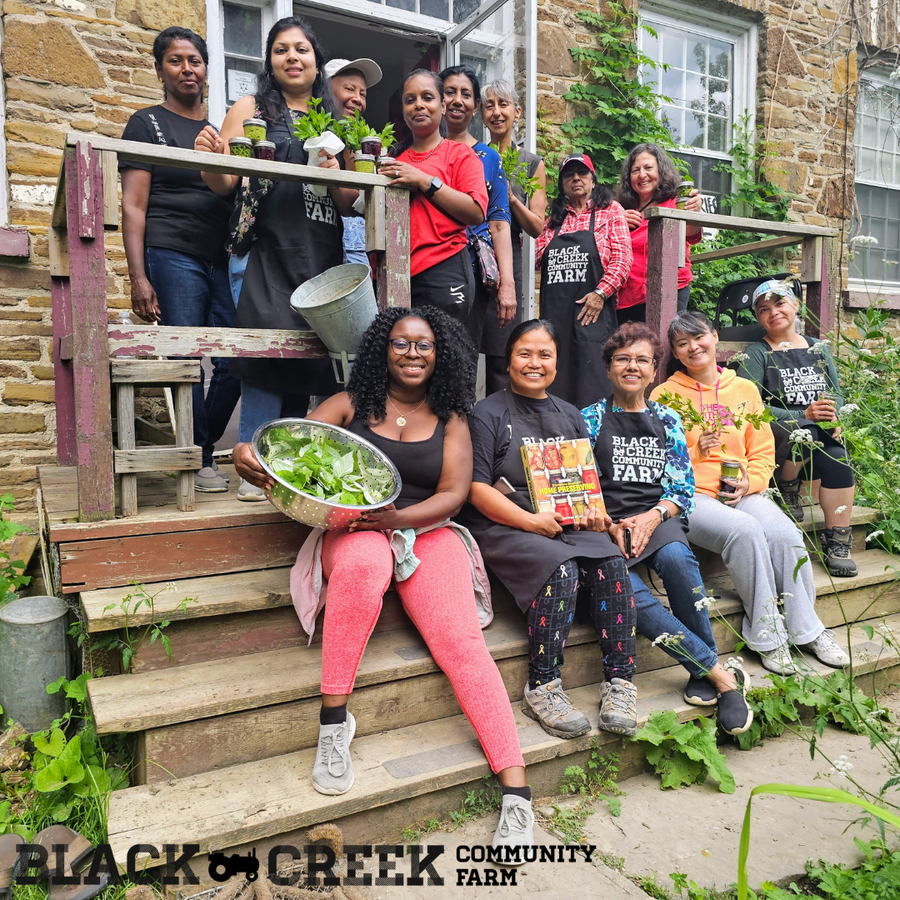

Black Creek Community Farm serves as a vital link between the community and the availability of culturally significant, nutritious food. Through initiatives such as offering affordably priced organic vegetable boxes and facilitating access to land for community members to farm foods that hold cultural significance, the farm fosters a deeper connection to both sustenance and heritage. The farm houses a diverse array of vegetables. The Bitter Melon, with its origins rooted in Africa, is a notable example. It is widely utilised in Southeast/South Asian cuisine and cultivated right here at BCCF. Other culturally relevant vegetables such as Gai Lan, White Garden Egg, Cucuzza, Okra, Long Bean, Bok Choy, and Tatsoi are also produced at the farm. Having a vast array of vegetables from different parts of the world allows frequent visitors of the farm to exchange cultural knowledge that helps foster a deeper understanding of global farming traditions.

While filming for the end-of-year giving campaign, I had the privilege of engaging in conversation with an elder from the community, a frequent visitor to the farm. In our discussion about the farm’s impact, she reminisced about her life in Guyana before immigrating to Canada, where she once had the opportunity to cultivate land for farming. However, upon settling in Canada, this aspect of her life became a distant memory. Yet, she described the farm as a transformative portal, evoking nostalgic memories of her homeland. It serves as a gateway to her past in Guyana, where she could grow vegetables not commonly found in local Canadian grocery stores.

The fundamental principle is clear: equitable access to nutritious, organic food, reflective of one’s cultural heritage, should be universal. No individual should be required to surrender the culinary essentials ingrained in their upbringing after enduring hardships.

Relevant sources:

- ‘We are in a crisis’: 1 in 10 Torontonians now rely on a food bank, new report finds

- The Science Behind the Three sisters

- Fighting For Food Justice In The Black Creek Community: Report, Analyses and Steps Forward

- Jane-Finch Consultation History

- Nutrition Recommendations Need To Be More Culturally Relevant—Here’s Why It Matters